How Taft's Gardens Grow

As John Taft enters his tenth decade, he reflects on the growth of his non-profit botanical gardens and his efforts to conserve Ventura County wildlands.

This story originally appeared in the summer 2024 issue of Ojai Quarterly.

How Taft’s Gardens Grow

“[My family left Missouri in 1922]. There were no paved roads except in cities. You can imagine how it was when they hit the edge of the city, then just set off onto a dirt road headed west…

“Dad said it took 22 days of travel to arrive at their final destination of Santa Paula, California. Dad’s brother had written to them about Santa Paula where orange and lemon trees were being planted by the hundreds of acres and work could be found in the orchards.” – John E. Taft.

John Earl Taft was born in Ventura in 1934. The eldest son of an avid hunter, Taft — who celebrated his 90th birthday April 18th — is a lifelong naturalist. He says he was born that way. One of Taft’s earliest memories is of walking hand in hand with his Grandma Jenny along Ventura Avenue, peering up at the hills.

“I would say ‘I want to go up there.’ [And] she would say, ‘No, you can’t — there are wild cattle up there.’ I can still feel her iron grip on my wrist. All I saw was the wild land and I wanted to be part of it.”

Taft’s parents worked for Shell Oil, John Taft Sr. as an electrician, and Virginia Taft as a switchboard operator. An early manifestation of their son’s passion for the wild was his fascination with hawks. “I read everything I could find on hawks,” Taft said, during an early spring conversation at the 264-acre Santa Ana Canyon nature preserve and botanical garden bearing his name: Taft Gardens and Nature Preserve. “I looked at everything that was printed, went to the library, [everything I read was] hawks, hawks, hawks.”

Taft recalls driving around east Ventura in the late 1940s in his father’s old pickup truck, the area was all “open land, canyons, and the like.” He delighted in climbing trees and collecting hawk’s eggs. Taft raised the chicks at his family home on Ventura’s Warner Street and trained the birds in falconry.

“My dad would say, ‘John Earl, if you keep messing with those hawks you’ll never amount to anything!’”

Taft spent his early years working for his father, who founded Taft Electric in 1946. The younger Taft ran Taft Sr.’s appliance store. “I got $2 a day when it first started. It was nice… [but] I wanted to be on my own. [I wanted] freedom.” In his spare time, Taft followed his passion for nature by documenting his beloved wild spaces on film.

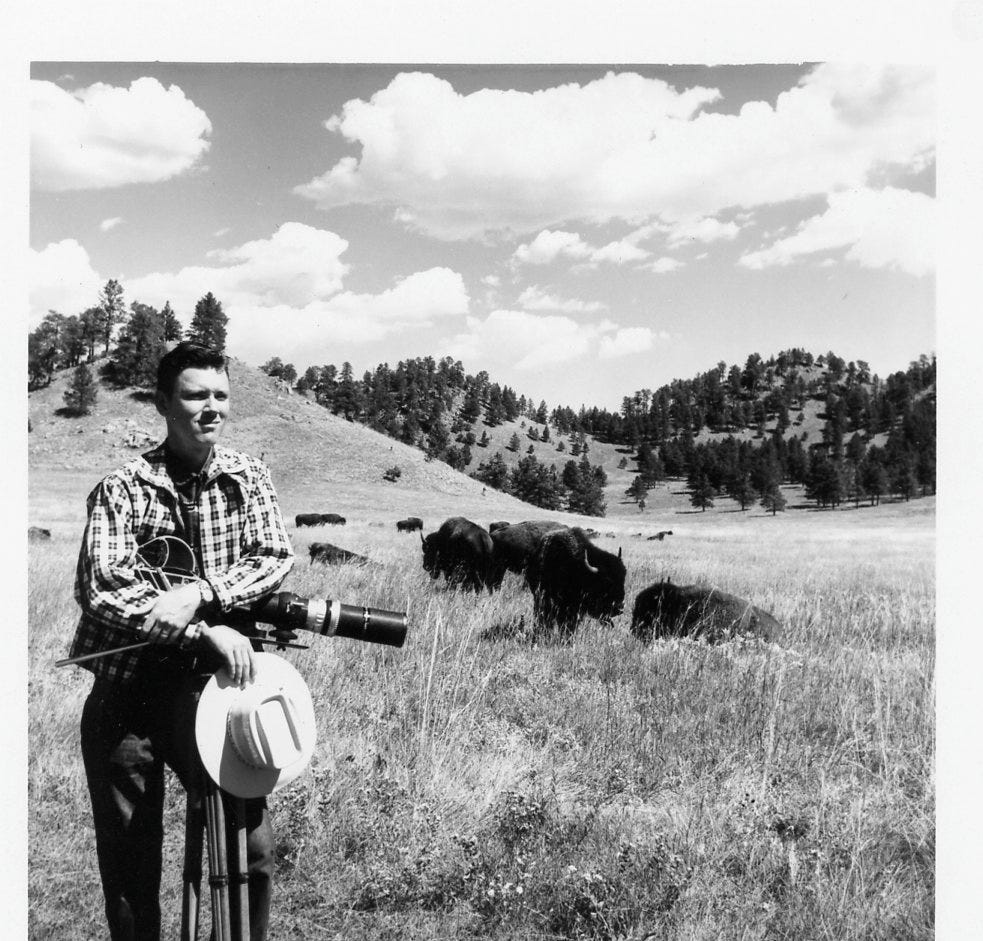

Taft met his first wife, Caroline, at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, where she worked as a taxidermist. They married in 1960. The same year, Taft began touring the country and making wildlife films with the National Audubon Society. By 1962, the first of Taft’s two daughters was born and the growing family was in search of a homestead. “We knew we wanted to build our life in the country,” Taft reminisced, “so we began searching up and down the coast for wild land that we could afford.” They eventually settled on the “tip top,” of the Ojai Valley’s Sulphur Mountain.

In 1964, Taft turned 30 years old. A few weeks later, Taft Sr. drowned in a fishing accident. In a way, Taft explained, his father’s sudden death set him free. By 1965, ownership of Taft Electric shifted and a new Taft Electric company was born. It still operates today. “I was free exactly at the time,” Taft said.

While Taft settled in Ojai, Ventura County was developing — rapidly. The area’s natural resources — oil, open land, fertile soil, and water — were highly valuable. As the Ventura County Star-Free Press commented at the time, the area is home to “the best undammed water source left in Southern California.”

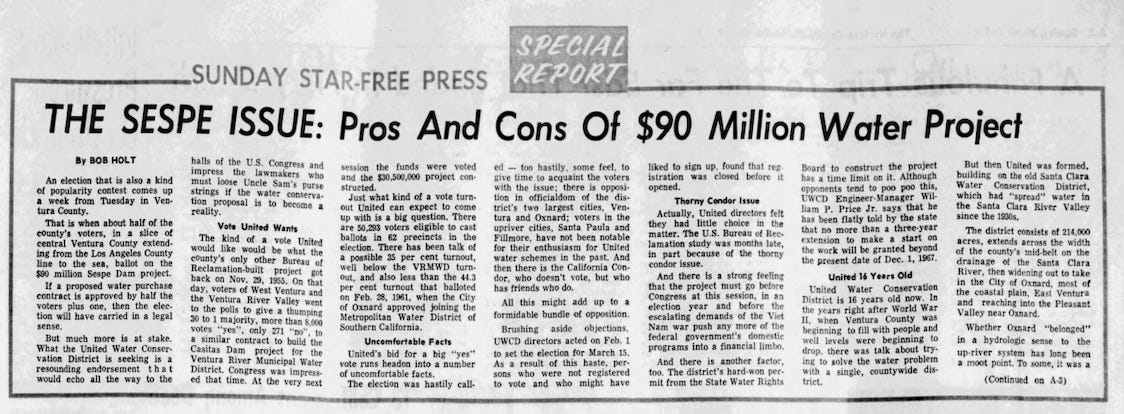

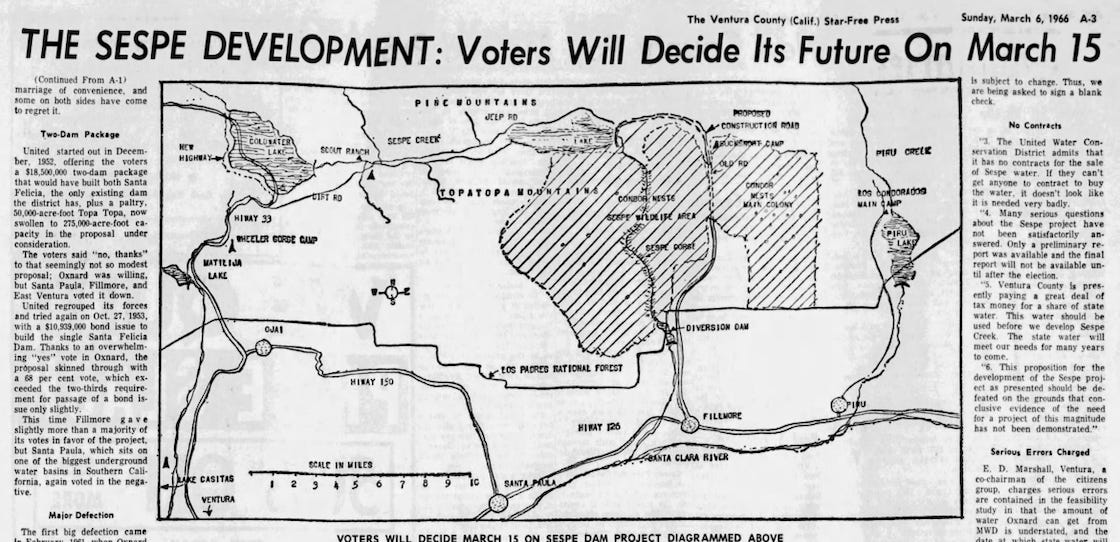

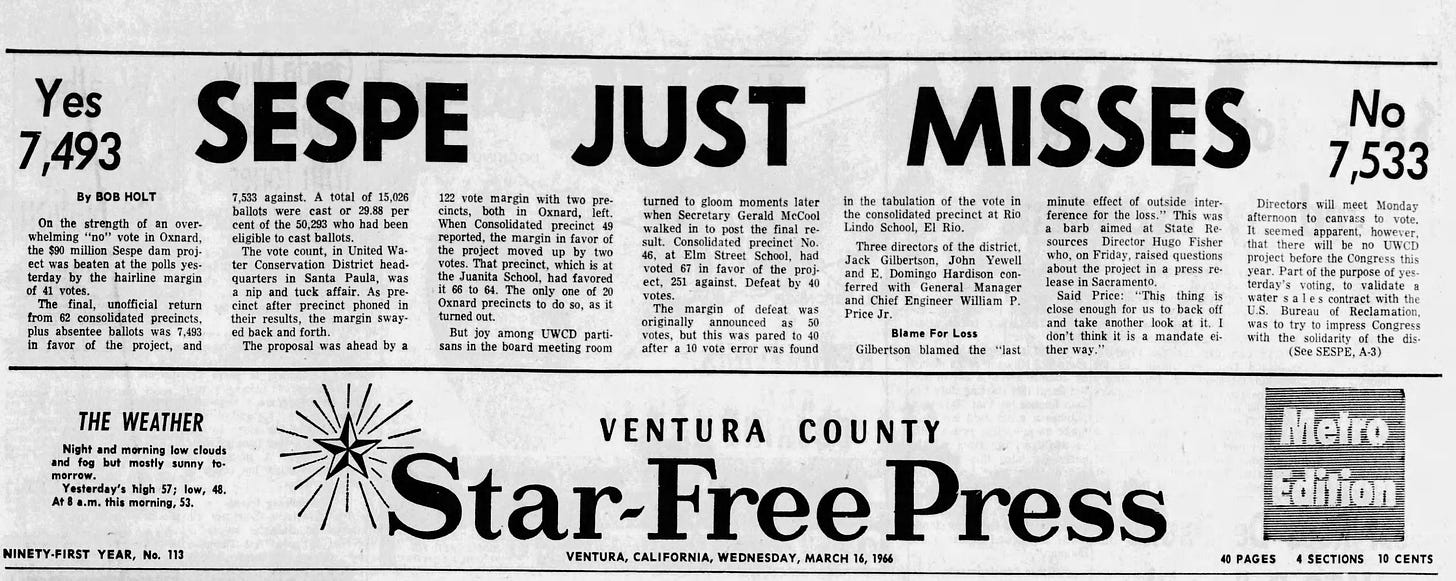

“There was a movement to build two dams in the Sespe Creek,” Taft explained. “They said, ‘We have to have more water to feed our citrus trees in Oxnard,’ basically.” In 1966, the United Water Conservation District sought voter approval of a $90 million “Sespe Dam Project.” The Star reported:

“The kind of vote United would like would be what the county’s only other Bureau of Reclamation-built project got back on Nov. 29, 1955. On that day, voters of West Ventura and the Ventura River Valley went to the polls to give a thumping 30 to 1 majority, more than 8,000 votes ‘yes’ and only 271 ‘no,’ to a similar contract to build the Casitas Dam project for the Ventura River Municipal Water District.”

Taft, then the leader of the Ventura Sierra Club, was predictably concerned about the Sespe’s resident bird of prey: the California condor. “The condors nested in the [Sespe],” Taft explained. “As you built the dam, you were going to destroy the condor.”

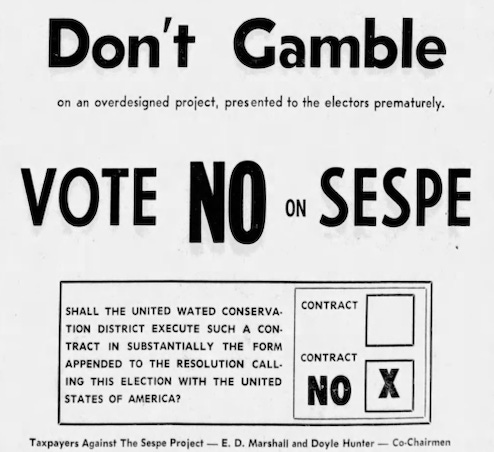

He also recognized local political realities: at the time, the condor’s plight didn’t necessarily move voters. In alliance with environmentalists like Gene Marshall and local Audubon groups, Taft formed an organization he thought would resonate with the electorate: Taxpayers Against the Sespe Project.

Taxpayers Against the Sespe Project spread their message in the Star-Free Press, arguing in advertisement form that the project was a “taxpayer boondoggle” that wouldn’t bring the prosperity United was promising.

March 15, 1966, the day of the special election, Taft and friends took their message directly to the voters. “[Gene Marshall] and I rented a megaphone on a car and drove up and down the streets,” he remembered. Taft and Marshall made announcements like, “You're going to have higher taxes: vote no on this scandalous operation!”

The next day, initial vote totals revealed a narrow defeat of the project. The final count showed a razor-thin margin of 32 votes. A recount later confirmed the proposed dams’ demise: 7,499 votes in favor and 7,531 votes against. Sespe Creek remains dam-free to this day.

As the Star-Free Press observed in 1966, “The California Condor… doesn’t vote, but has friends who do.” Thirty-two votes altered the history of Ventura County.

Development loomed in the Ojai Valley, too.

As former Ventura County Supervisor Ralph “Hoot” Bennett observed in late 1968, “Ventura County had a population of 18,000 [In 1912]. By 1968, the population numbered 340,000 people and as of today, it numbers 360,000. That means 20,000 people… moved into Ventura County in the past six months. Those people moved in without a decent road in the area, no planning of the road system.”

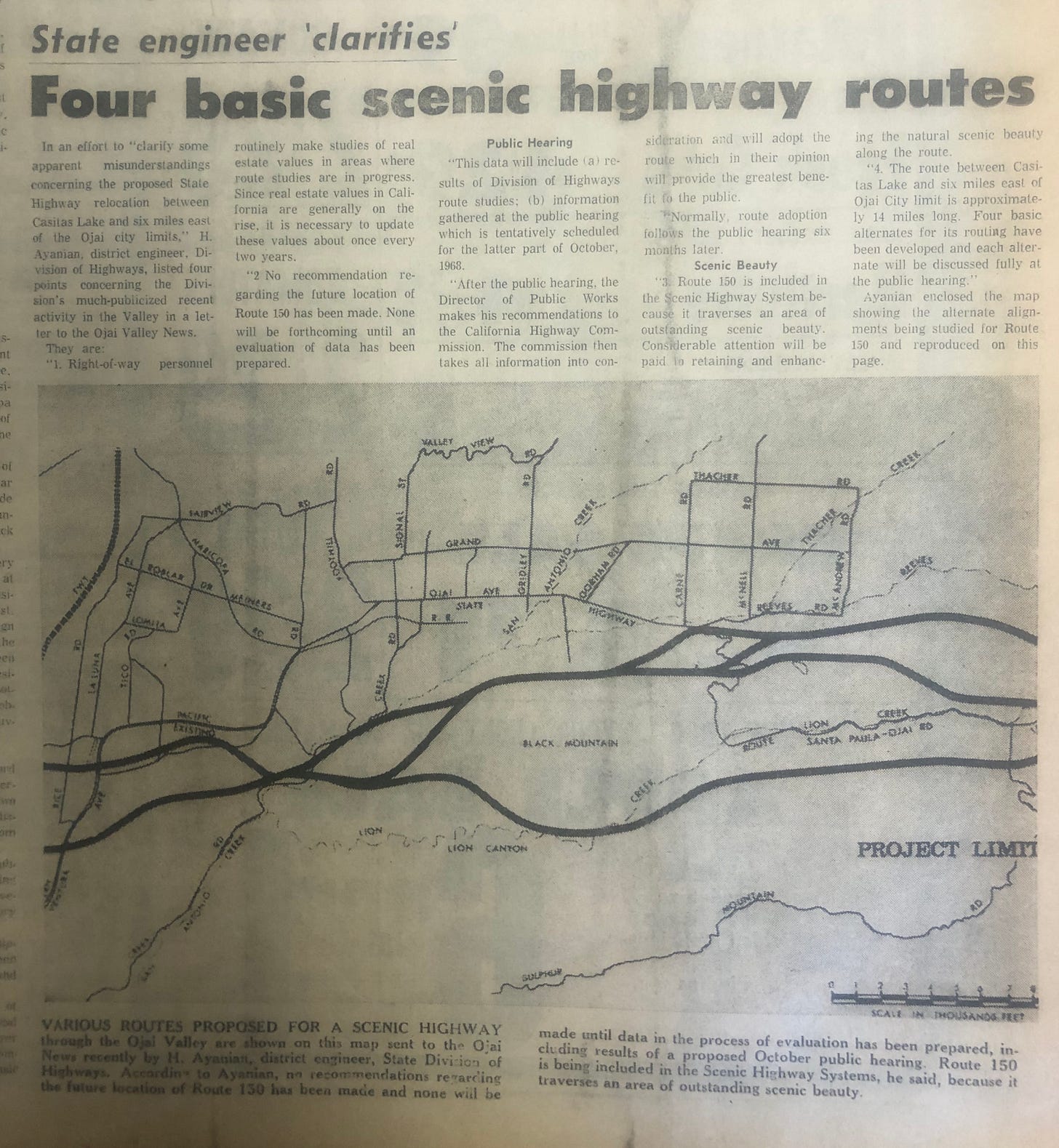

In the Ojai Valley, that lack of transportation planning manifests on Ojai Avenue: the primary thoroughfare through the city is also designated as State Route 150. By the early 1960s, the State Division of Highways (today known as CalTrans) began studying alternate routes through the valley — an alternative “scenic highway,” or, as some residents feared: a freeway running right through what was then a community of 5,000 people.

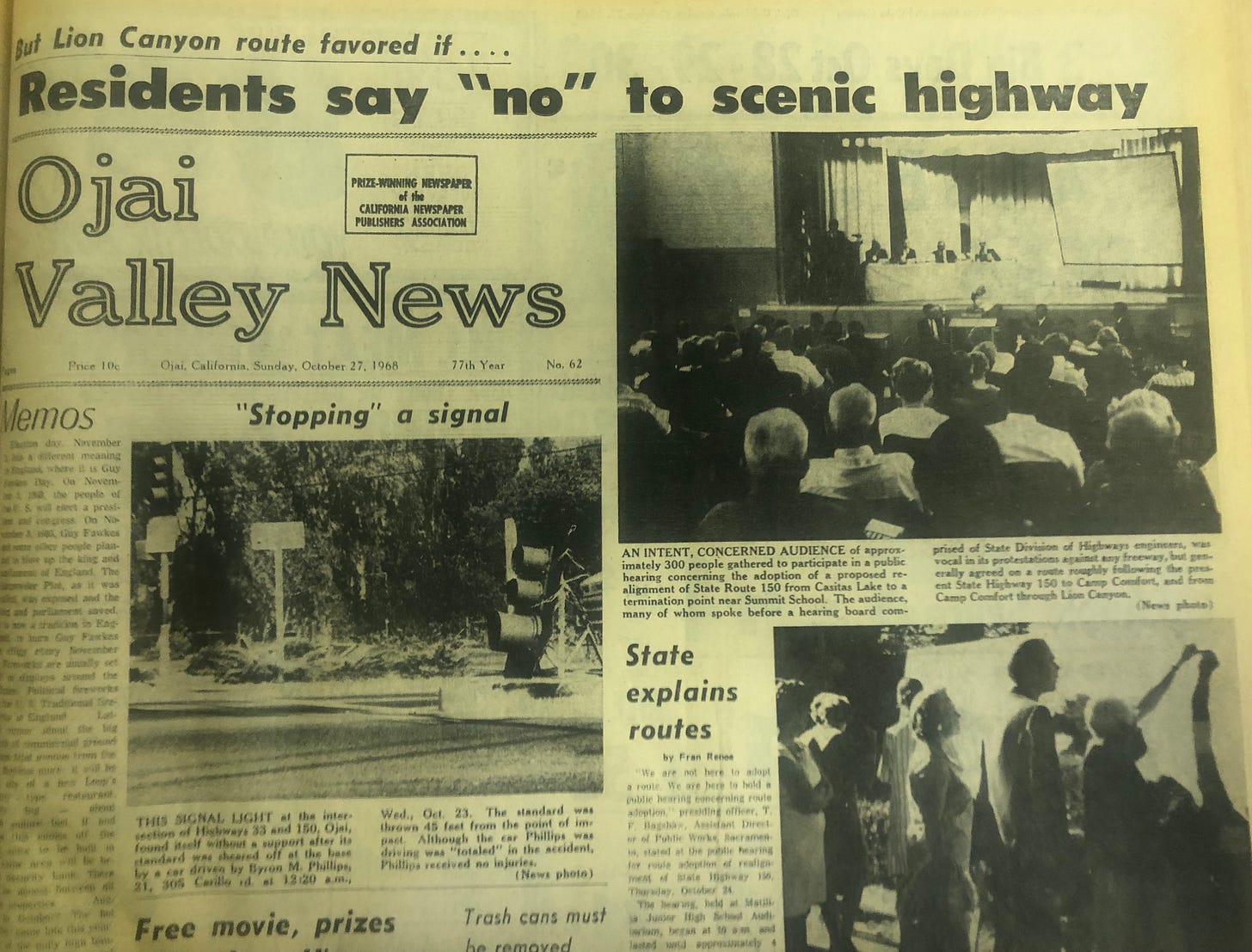

“I saw the [Ojai] City Council excited about it,” Taft recounted while cruising Taft Gardens in his golf cart, “so we decided that the City Council had to be changed.” That conversation marked the formation of another highly impactful local political group: the Citizens to Preserve the Ojai. Their efforts are described in an October 1968 edition of the Ojai Valley News:

“The [Citizens] to Preserve the Ojai, a group originally formed to block route adoption of Highway 150 into a scenic highway, is making a last-ditch stand with a petition that will seek to convince the state that a large number of residents in the Ojai Valley prefer no action by the state at this present time.”

Now, theirs was not your average petition. As Taft will tell you, “A petition is worthless. Anybody will sign a petition.” Instead, the Citizens hired an engineer to draw a parcel map of the entire Ojai Valley. They surveyed every household in the valley and marked those opposed to the proposed freeway on the map in red.

“At the final Board of Supervisors hearing [on the matter] we presented the map, which was entirely marked red except for one five-acre parcel owned by a City Councilman,” Taft recalled. “It was clear the public did not support the freeway so the Supervisors voted it down.”

A November 13th, 1968 Ojai Valley News article tells a similar story: “If any Ojai residents are in favor of the proposed scenic freeway for the Ojai Valley, there was no evidence of it at the Board of Supervisors yesterday.”

By 1969, the State was expected to “close out route studies on the 14-mile section of the proposed Route 150,” according to Ojai Valley News reporting at the time. “In the end, for the first time ever in California, the State Maps were revised with the removal of the freeway to Ojai,” Taft said.

As the decade came to a close, Taft acquired the wildland property of his dreams in Santa Ana Canyon near Ojai’s Lake Casitas (the result of the 1955 voter-sanctioned dam). It would become the Taft Gardens and Nature Preserve. Initially, Taft considered developing the property into a campground for Casitas visitors. Later, he thought the land could host an orchard (and create an additional income stream).

“I brought in a professional to visit the property,” Taft recalled. “He said the land was suitable for 75 acres of orange orchards. But as he was leaving he turned to me and said, ‘But that would be a shame, wouldn’t it?’ I remember thinking that might have been the voice of providence.”

“Next I investigated planting an avocado orchard,” Taft continued. “I found a man who agreed to plant 18 acres of avocados where the [botanical] gardens are now. But something happened and he never came to do the work. I called him a few times and he said he was coming, but never did. I took that as a sign. It was the end of my agricultural aspirations for the land.”

Divine providence acted again, according to Taft, a few years later while he was tending to the cabbages in his Sulphur Mountain garden. This time, however, providence came via a voice in his head. He heard the words, “‘Go back. You have to go back to Ventura.’” Taft stopped. He looked around, and thought, ‘What does that mean?’

Taft followed the mysterious command, drove his truck through the Ventura plains, and decided to follow a billboard that read “For Sale: 47 Acres.” Taft came across the owner and learned the land was home to an old walnut orchard. Suddenly, he realized why the parcel felt familiar: his grandfather was once the steward of this very orchard. Sensing fate, Taft — alongside a partner from Taft Electric, Bud Hartman, — ultimately purchased 170 acres of land in what would become downtown Ventura.

It’s one of “a hundred” cases of destiny he’s experienced in his life, Taft said. “I had to go back and then everything clicked into place,” he said, gesturing at the Taft Gardens.

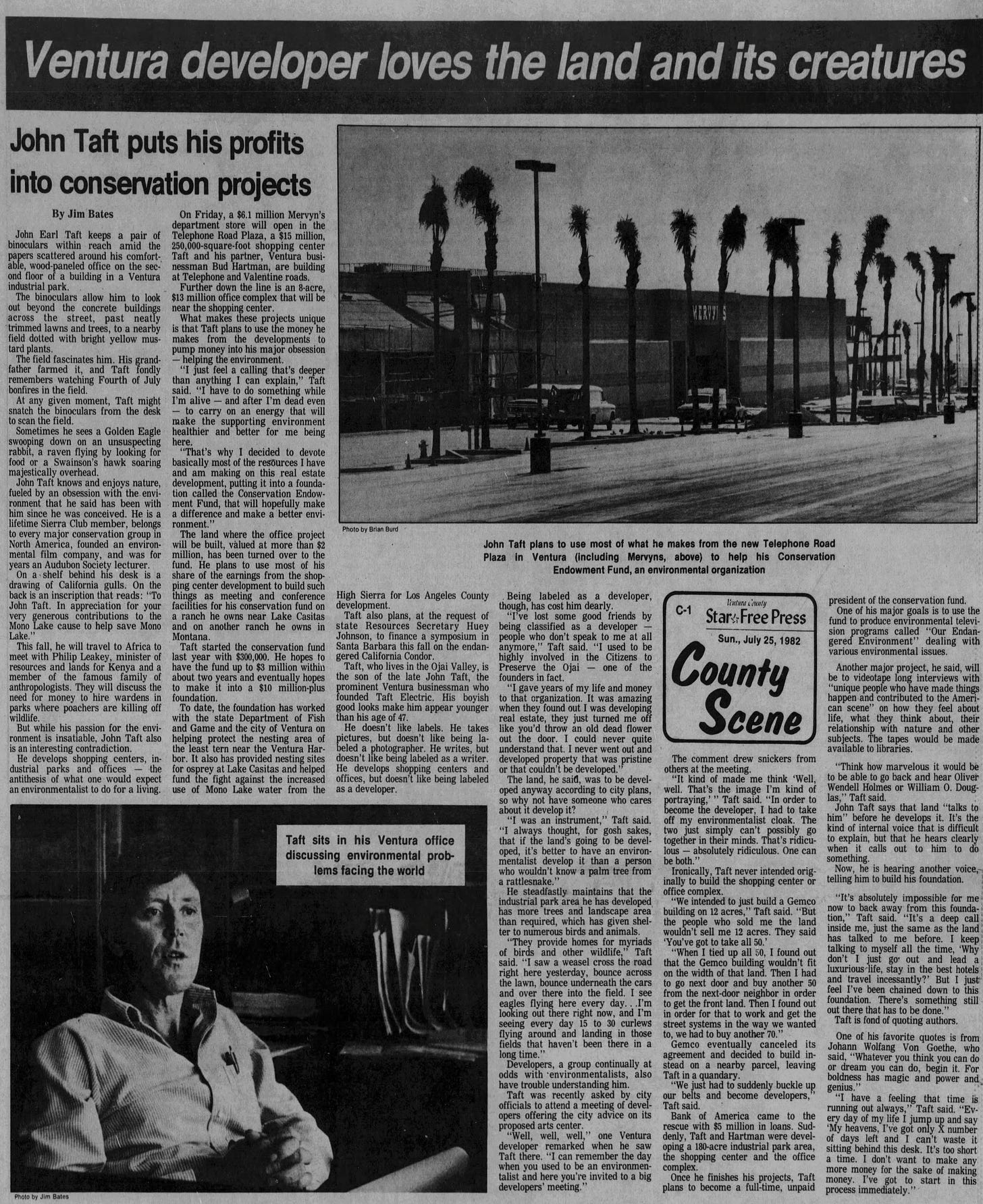

The next decade of Taft’s life mirrored the story of the growing county. Acreage he purchased along Ventura Avenue became lucrative commercial property for heavy industries like welding, fabrication and oil field services. In 1982, Taft and Hartman opened a $15 million, 250,000-square-foot shopping center in Ventura: Telephone Road Plaza.

What made the shopping center project unique, according to a July 1982 article in the Star, “is that Taft plans to use the money he makes from the developments to pump money into his major obsession — helping the environment. ‘I just feel a calling that’s deeper than anything I can explain,’ [Taft] said.”

Using profits from the development, Taft poured resources into the Conservation Endowment Fund — the nonprofit organization that funds the Taft Gardens and Nature Preserve’s activities to this day. Following the success of his development activities, he added a world-class botanical garden featuring his favorite plants from Ojai’s “sister climates” in Australia and South Africa. Taft protected the remaining 200 acres of the property in a conservation easement with the Wildlife Land Trust.

Still, his business activities cost him some old friends.

“‘I’ve lost some good friends by being classified as a developer — people don’t speak to me anymore,” Taft told the Star-Free Press. “I used to be highly involved in the Citizens to Preserve the Ojai — one of the founders in fact. I gave years of my life and money to that organization. It was amazing when they found out I was developing real estate, they just turned me off like you’d throw an old dead flower out the door. I could never quite understand that. I never went out and developed property that was pristine or that couldn’t be developed.’ The land, he said, was to be developed anyway according to city plans, so why not have someone who cares about it develop it?”

As the botanical garden matured and Santa Ana Canyon recovered from a devastating fire in 1985, Taft, alongside his second wife Melody, founded The International Center for Earth Concerns (ICEC). During the nineties and early 2000’s, ICEC hosted thousands of local schoolchildren at the gardens and nature preserve — including your author. ICEC also donated a “floating classroom” to Lake Casitas. The classroom — managed by the Rotary Club of Ojai West — floats on Lake Casitas to this day. The days of bringing busloads of young students to the garden, however, are over due to traffic complaints from neighbors. That’s one of the first challenges Taft’s granddaughter, Jaide Whitman, confronted when she took over management of the Conservation Endowment Fund in 2019.

Whitman, the daughter of Julia Taft Whitman, was born and raised in Santa Ana Canyon. As a child, Whitman didn’t have neighbors to play with, but acres of wilderness to explore.

“I had to entertain myself in nature,” Whitman said. “It created a sense of closeness and a sense of relationship. Now, if I'm out in nature, I don't feel alone. I don't get lonely because I have that deep connection with place.”

Whitman aims to share that feeling of connectedness in nature with the broader community. “What we have and what I've been born into and the position that I've stepped into comes from a place of enormous privilege,” she reflected. “My vision is about, how do we protect this and how do we share this?”

Whitman is not alone in carrying her grandfather’s work forward: her cousin, Alexandra Nicklin (daughter of Jenny Taft) is the Garden’s visitor coordinator. Whitman and Nicklin share a particular passion for restoration projects that highlight larger environmental challenges.

In 2022, the cousins planted the Taft Pollinator Garden to raise awareness about declining pollinator populations nationwide. They’re now hard at work on white sage and milkweed restoration projects in the nature preserve. October 2024 will be branded “Monarch Month” at the Taft Gardens to draw attention to the monarch’s plight. (October 2023, delightfully, was known as “Oaktober”).

“[Our grandfather] put his heart and soul into the botanical garden,” Whitman said. “So it kind of feels like Alexandra and I are putting our heart and soul into the nature preserve.”

In 2020, Whitman partnered with local artist Cassandra C. Jones to establish the Taft Gardens’ Art in Nature residency. Eighteen local artists have created original work in the gardens since the program’s founding. Whitman has also reimagined her grandfather’s educational programming in partnership with local native plant educator Lanny Kaufer and Elena Rios, a nature connection guide and cultural practitioner.

With his granddaughters now running the nonprofit, Taft spends much of his time cruising the gardens in his golf cart. He loves to greet visitors, share stories, and offer rides around the property. He brushes off words of thanks, though. “You'd never thank a person for doing what he's inclined to do,” Taft says. “Thank me when you see me mopping floors or painting walls, but not for saving nature.”

To learn more about the Taft Gardens and Nature Preserve or schedule a visit, go to: taftgardens.org.