The Crisis Outside City Hall

An in-depth exploration of homelessness in Ojai and a forthcoming Supreme Court case that could change everything. Plus: get to know a few locals camping outside City Council Chambers.

Greetings, readers! The story that follows is a deep dive into homelessness.

I am making this article available to the public for a limited time. If you find this work valuable, please consider purchasing a subscription. You can also make a donation to support longform journalism for the Ojai Valley.

Before reading, I recommend settling in. Because, friends, we’re going on a journey.

The Crisis Outside City Hall

It’s a daybreak in downtown Ojai. The temperature is 44, the sky is a shocking shade of pink, and I’m sitting in the passenger seat of Ventura County Sheriff’s Office (VCSO) Dep. Christian LaSecla’s police cruiser. We’re two in a group that includes a dozen volunteers, members of VCSO’s Homeless Liaison Unit1, and HELP of Ojai2 staff. We gathered at dawn in the HELP of Ojai parking lot, grouped into teams, and dispatched with a single mission: find and survey the Ojai Valley’s homeless3 population.

This is the 2024 Point in Time Count, a massive survey of homelessness that took place in communities across the nation on January 24th. Once collected, data is sent to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), crunched, and then issued publicly as part of an Annual Homelessness Assessment Report to the U.S. Congress. Annual Point in Time Count data — critically — is used to determine eligibility for state and federal funding.

Dep. LaSecla, myself and two fellow (civilian) volunteers were assigned to survey unhoused folks in the area between Oak View and the former Petrochemical Co. refinery site near Highway 33. I can’t get into details about the individuals we surveyed, but you’ll have the opportunity to get to know a few members of Ojai’s homeless community later in this story.

I can share that I personally surveyed seven men, the majority of whom had long histories in the Ojai Valley. Some lived in tents, others in cars or campers. I met one man had who spent the night under Highway 33. Most of the men I spoke to had been homeless for more than a year. Many have a chronic illness, and a few acknowledged addiction issues. One young man lives in a tent pitched less than a mile from his family home.

The best information we have about the local homeless community, however, is from last year: the 2023 Point In Time count. Let’s get into the numbers.

HOMELESSNESS IN OJAI, VENTURA COUNTY, AND ACROSS THESE UNITED STATES

Homelessness in Ventura County increased by 10% between 2022 and 2023. This is far from the sharpest increase on the books, though. Between 2018 and 2019, homelessness in Ventura County increased by 29% — that’s 370 people. The county saw a similarly drastic increase in homelessness between 2020 and 2022 — the pandemic years — with an increase of 25%, or 495 unhoused people. According to the most recent national report on homelessness, California is home to 28% of all unhoused people in the United States. Further distinguishing California is our community of “unsheltered” individuals. “Unsheltered homelessness” — as defined by the federal government — refers to folks sleeping in cars, campers, tents, or on the streets.4 All of the folks I spoke to during the Point in Time count, for example, are unsheltered. The 2023 count revealed that a majority — nearly 70% — of California’s homeless community is unsheltered. In fact, California is home to nearly 50% of the United States’ unsheltered homeless population.

To be clear: homelessness is not solely a California problem, though the Golden State is certainly leading the nation on this one. The first line in the 2023 homelessness assessment report to Congress is this: “On a single night in 2023, roughly 653,100 people – or about 20 of every 10,000 people in the United States – were experiencing homelessness.”

Let’s look at this horror on a hyperlocal level. In the City of Ojai, our homeless population is actually on a slight downturn. In 2020, 49 homeless individuals lived in the City of Ojai. By 2023, that number decreased to 44. Interestingly, the available data shows that Ojai’s homeless population peaked in the first year of data collection. In 2007, the City of Ojai was reportedly home to 82 individuals experiencing homelessness.

But, as residents of this little valley know, the community known as “Ojai” spreads far beyond the 4.5 miles of the city and into unincorporated Ventura County.5 The 2023 Point-in-Time count identified 69 unsheltered people in the unincorporated area. We can’t be sure how many of those folks reside in the Ojai Valley. That said, we do have one data point on homelessness in the wider valley. According to Ojai Unified School District (OUSD) Student Services Coordinator Alexandra Mejia-Holdsworth, 47 local students (and, presumably, their families) are struggling with homelessness. That’s 2% of Ojai’s public school population.

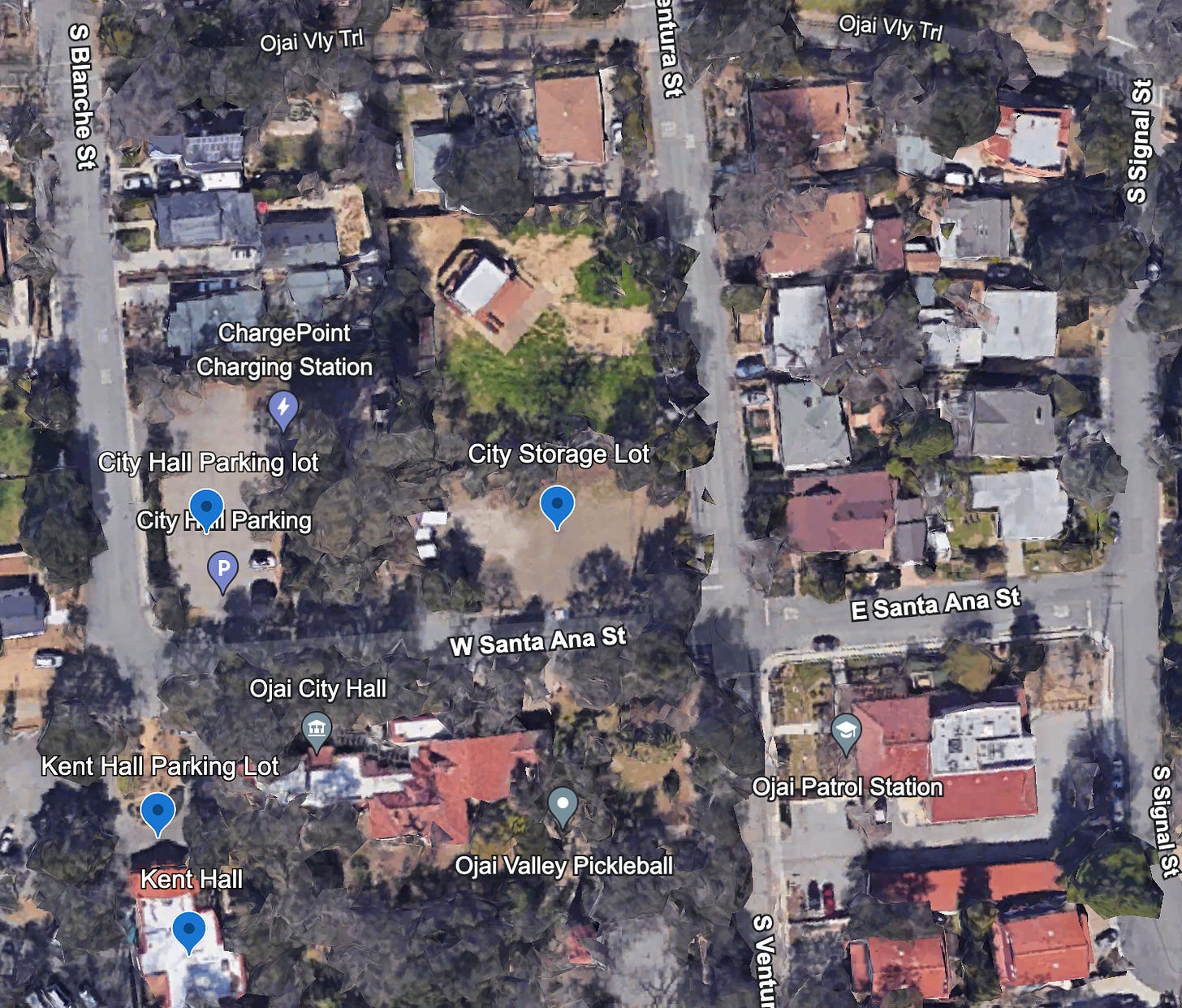

The most visible example of homelessness in Ojai, of course, is located at City Hall: a potent symbol of the housing emergency. Adjacent to the public pickleball courts and the Ojai Community Demonstration Garden is a homeless encampment of approximately 30 people — that’s according to Rick Raine, a long-time Ojai resident who was hired to manage the camp late last year.6

The Ojai City Hall campus features eight acres of open space and oak woodland. Middle Stewart Canyon Creek runs through the property — which is why many of the campers’ tents are erected on a slope (and why the camp is a challenging environment in a rainstorm). The area has long been home to a small unhoused population — or, so I’m told — but the current encampment is unprecedented.

How did the camp become so large, so quickly? Here’s the short version, according to William Holden, an Ojai resident who resides in the City Hall camp.

“I did this,” Holden said, addressing the Ojai City Council in September 2023. “I’ve invited these people who were sleeping in their cars, those people that are under the bridge, to come back here, because I’ve heard the police are not making us move… So this [population] swelling is not… coming down from Santa Barbara. No. These are people that were sleeping next to Westridge and in Libbey Bowl and other places and they’re here now. It’s not new. This is your old problem that’s come home to show you that it’s a real problem.”

There are two points in Holden’s statement that I want to dig into. First, let’s discuss the law enforcement piece. Because he’s right: VCSO — by and large — is not making anyone leave the camp. And that’s part of the sea change in California’s homelessness crisis.

MARTIN V. CITY OF BOISE

At this point in the story, we must take a brief detour to Idaho. In 2009, the City of Boise had ordinances on the books that banned the act of sleeping in public.7 (We have a very similar law in Ojai, we’ll get into that later.) According to the Harvard Law Review:

“One [Boise] ordinance banned ‘[o]ccupying, lodging or sleeping in any ... place... without...permission’; another barred the ‘use [of] any...streets, sidewalks, parks or public places as a camping place at any time.’ [Under these laws], Janet Bell was cited twice, once for sitting on a riverbank with her backpack, [and] another time for putting down a bedroll in the woods. She pled guilty and received a thirty-day suspended sentence. Robert Martin, who has difficulty walking, received a citation for resting near a shelter. He was found guilty at trial and charged $150.”

Ultimately, Bell, Martin, and nine other homeless Boise residents filed suit against the City of Boise. They argued that the local law violated their Eighth Amendment rights by subjecting them to “cruel and unusual punishment.”8 Ultimately, the case — known as Martin v. City of Boise — made its way to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals — a federal appeals court with jurisdiction over the western United States. Here’s what Judge Marsha Lee Berzon wrote in her 2019 opinion:

“The Eighth Amendment prohibits the imposition of criminal penalties for sitting, sleeping, or lying outside on public property for homeless individuals who cannot obtain shelter… as long as there is no option of sleeping indoors, the government cannot criminalize indigent, homeless people for sleeping outdoors, on public property, on the false premise they had a choice in the matter.”

Judge Berzon’s opinion carries the force of law in the Ninth Circuit.9 Martin v. City of Boise set a critical precedent, one that has prevented western municipalities from forcibly relocating (or, “sweeping”) homeless individuals from encampments when they (the municipality) has no shelter to offer. The Martin v. Boise precedent has proven hugely impactful, for California in particular. (Remember: the majority of California’s homeless population is unsheltered — they live primarily outdoors).

Another legal fight over the rights of unhoused individuals began six weeks after the Martin decision — this time in Oregon. The case, Johnson v. Grants Pass, challenged “municipal ordinances [in the City of Grants Pass, Oregon] which, among other things, preclude homeless persons from using a blanket, a pillow, or cardboard box for protection from the elements while sleeping within the City’s limits.”10 In an opinion authored by Judge Roslyn Silver, the Ninth Circuit affirmed that the Grants Pass ordinances, like those in Boise, violate the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Silver wrote:

“The only plausible reading of [Martin v. Boise] is that it applies to the act of “sleeping” in public, including articles necessary to facilitate sleep… The City’s position that it is entitled to enforce a complete prohibition on ‘bedding, sleeping bag, or other material used for bedding purposes’ is incorrect… Plaintiffs such as [Johnson] are not voluntarily homeless and… the anti-camping ordinances are unconstitutional as applied to them unless there is some place, such as shelter, they can lawfully sleep.”

… And that’s when the City of Grants Pass petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to consider the case. They’re far from the only municipality pleading for Supreme Court intervention — even California Governor Gavin Newsom11 has registered his opposition to the Martin v. Boise precedent.

And on January 12th something big happened: the Supreme Court agreed to take the case.12 Newsom — for his part — welcomed the news.

“California has invested billions to address homelessness, but rulings from the bench have tied the hands of state and local governments to address this issue,” he said in a statement. “The Supreme Court can now correct course and end the costly delays from lawsuits that have plagued our efforts to clear encampments and deliver services to those in need.”

“It’s understandable that [Newsom and others] want more power to deal with the problem of homelessness,” wrote Berkeley Law School Dean Erwin Chemerinsky in a Los Angeles Times op-ed. “But the solution can’t be punishing or criminalizing homeless people.” Considering the forthcoming Supreme Court decision, Chemerinsky wrote, “there is every reason to fear that the conservative justices will allow governments to criminalize sleeping in public spaces even if people have nowhere else to go.”

Now, my friends, with all of this in mind, let’s take a look at a section of Ojai Municipal Code:13

“It shall be unlawful for any person to sleep, camp, occupy camp facilities or use camp paraphernalia in the following areas, except as otherwise provided for: any street; and any public parking lot or public area, improved or unimproved.”

In the wake of Martin v. Boise and Johnson v. Grants Pass, it is arguable that this section of Ojai’s municipal code is unconstitutional.

LOCAL ENFORCEMENT

When I visited Ojai Police Chief Trina Newman for an interview, she greeted me with a tall stack of papers: the text of the Boise and Grants Pass cases. Newman, who was appointed to her post one year ago, is the first female police chief in Ojai’s history. She has 25 years of experience with VCSO. “We've had to shift our thinking in how we have addressed homelessness,” she reflected. “Ten years ago, we would go and just kick everybody out and not even think twice about it.”

VCSO, Newman said, responds to issues in the City Hall camp ranging from excessively loud music to an assault with a deadly weapon.14 I should note that the Ojai Police Station is literally across the street from City Hall.

“[The campers] congregate in that area because it feels safe for them to be there in numbers,” Newman explained, reflecting on the population living at City Hall. “But at the same time, they all are struggling with their own issues and trying to live amongst each other with those issues. So it's difficult and it creates problems. We have had calls for batteries and assaults [at the camp].”

Much of what Newman said corresponds with what campers have told me. In general, they have a strong community that looks out for one another. I’ve also heard accounts of theft, drug abuse, and an assault. There’s apparently one notorious camper — a man with a large (and expanding) camp footprint — who plays loud music at all hours.

In the words of one woman, Diane, who lives at City Hall, “there’s more good than bad,” she said, describing the strong relationships she has with other women in the camp, but, “there’s a couple of bad apples raising hell.”

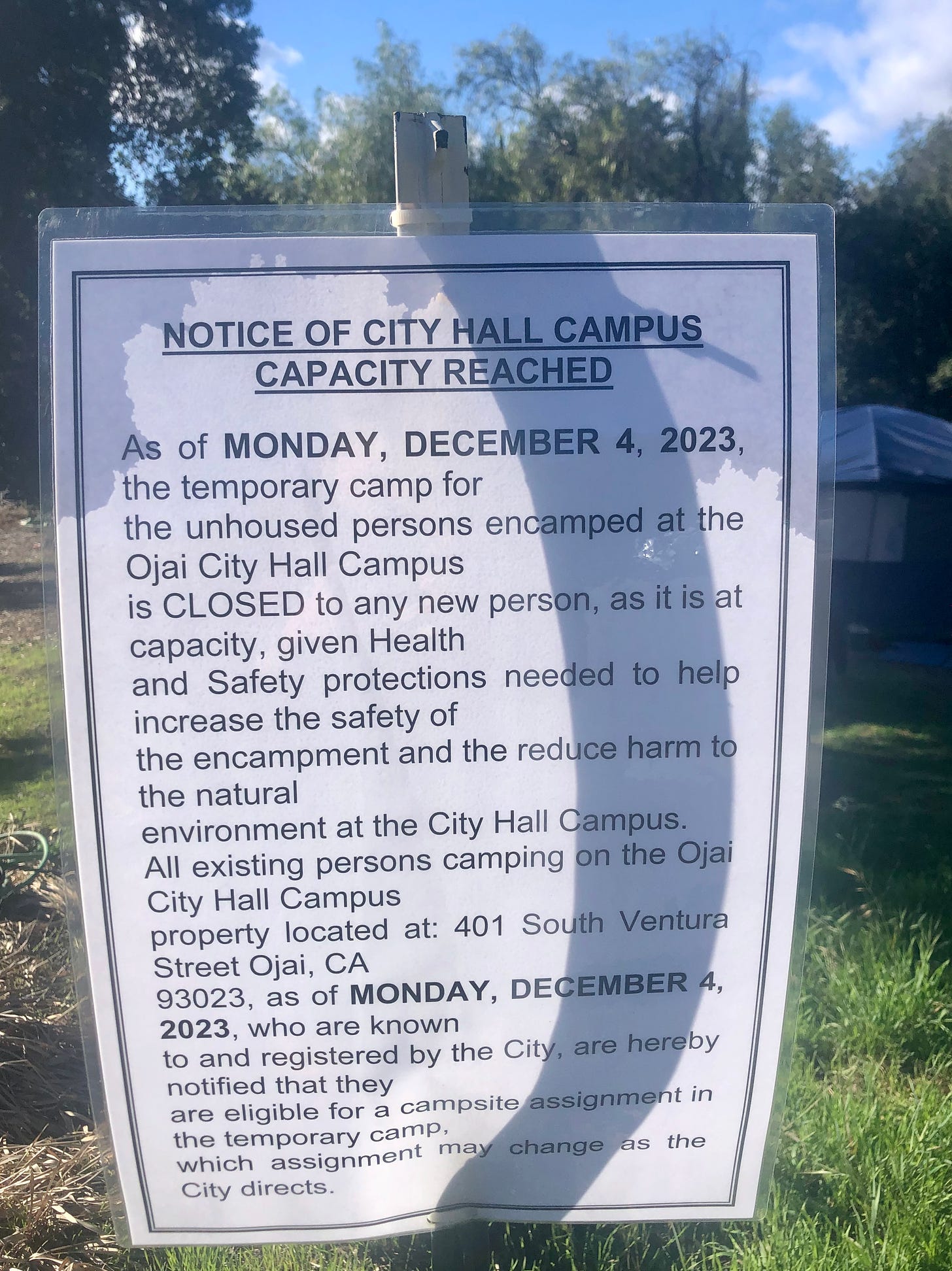

As of Dec. 4th, the camp at City Hall was declared “closed” to any new campers. “I hate to say this, but the reality of it, is that we can't enforce anything,” Newman said. “We can't prevent people from coming. And we can't say that if someone were to come in today and start setting a camp, we can't say, ‘nope, you cannot be here.’”

According to Newman, the only time law enforcement can force an individual to relocate is, “if they are impeding ingress and egress to or from businesses or public right of ways such as streets [or] sidewalks.”

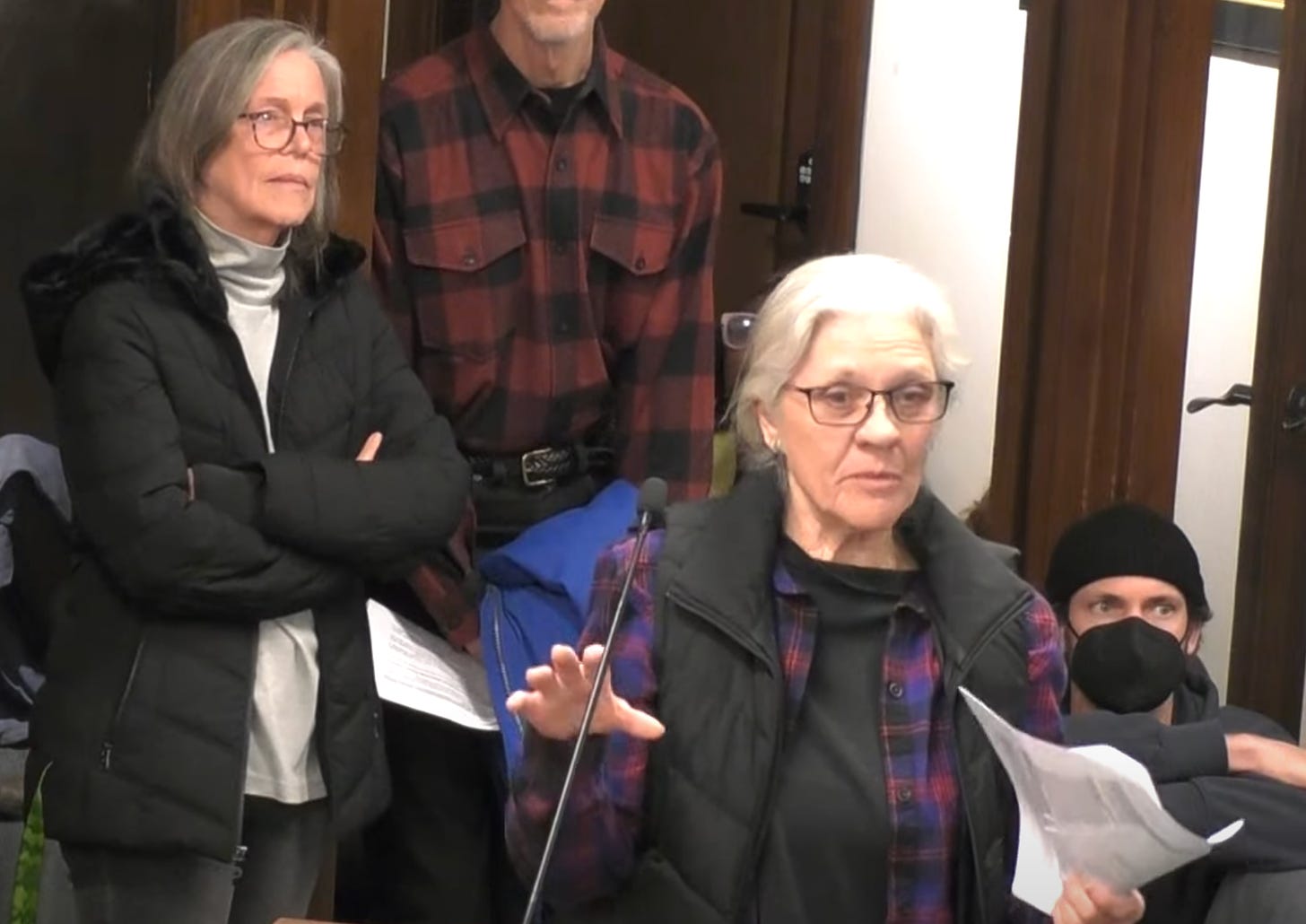

And that, folks, is the Martin decision in action. As the leader of Ojai’s Homeless Taskforce, Ruth Miller said during a recent City Council meeting, “the law as it stands gives only one option to dismantle encampments, and that is to provide housing.”

Let’s now explore Holden’s second assertion: that the City Hall camp is primarily occupied by locals.15 I posed the question to Raine, who has managed the camp since October. “I haven't done background checks,” he said, “but I knew a lot of them when I was running the Ojai Valley Family Shelter.” One camp resident, he added, “used to live right up the street from me.”

Jayn Walter, co-executive director of the HELP of Ojai provided a similar perspective, noting that the majority of the camp residents are HELP clients. According to a city report, ten women and twenty men currently reside in the camp. The majority, 60%, have disabilities or a chronic health condition.

The city, too, recently acknowledged the campers’ local roots. As (now former) Interim City Manager Carl Alameda wrote in a recent staff report, “the individuals living within the encampment are longtime Ojai unhoused, they are largely not from outside the city. Most of these individuals previously slept in Ojai City parks, under street overpasses, commercial areas, and vacant properties.”

Let’s consider this question answered. Now, let’s get to know a few of the campers.16

Kristen Wingate graduated from Nordhoff High School in 1989. Today, she lives in a tent at City Hall with her bulldog, Roscoe. Locals may remember Wingate from Ace Hardware, where she worked as a cashier. She left the job due to a spinal fusion surgery and went on state disability, she explained. During that time, Wingate’s long-term rental housing was sold — she was paying $1,400 a month.

“[State disability] only goes for a year. And then if you're going to be out longer, they tell you to apply for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI),” she explained. Wingate’s SSDI application was denied, and she’s appealing the decision. Due to her disability, she is still unable to work. Without disability benefits, she has no income.

Wingate told her story surrounded by all of her possessions, much of which have been damaged by rain.17 She was born and raised in Ojai, she said. She remembers her grandfather telling stories of Ojai Avenue as a dirt road.

“It's embarrassing to be out here,” she confessed. I asked her what she wants the community to know about her experience.

“Everybody automatically assumes we’re all drug addicts and it's not the case. This is the first time I've ever experienced homelessness and it's not easy. People take for granted [things like] how do you wash your clothes? Where do you brush your teeth? Are you able to shower?”

Prior to living at City Hall, Kristin spent many nights in her car, often parked outside the local Vons. “Sometimes I'd drive to Ventura, but usually [I stayed in] Ojai because I felt safe in Ojai.”

Danielle Alstot, 38, lives at City Hall with her partner, Josh, 35. Their tent is pitched just above Middle Stewart Canyon Creek. (Raine has asked them to move, Alstot admitted). “I wanted to be away from the chaos,” she said, gesturing to a collection of tents further up the hill where, Alstot says, drug use is common.

Alstot works part-time at the Ojai Valley Athletic Club as a housekeeper but, “I can't afford $1,300 a month for a room in someone's house,” she said. Josh has an income too — he works at Taco Bell.

Alstot — who is a passionate artist — moved to Oak View with her family when she was two years old. Her first memory, she said, is of that house in Oak View. She graduated from Ventura High School in 2004. Alstot and Josh have lived at City Hall for the past four months, she said, alongside their two cats.

Jaime Nelson, 74, raised two children in Ojai. Her grandchild attends OUSD. Once her kids became adults, Nelson began splitting rent payments with her daughter and her daughter’s boyfriend. When the couple broke up, Nelson was left in the home on her own, unable to afford the rent. She then decamped to Texas, where her son lives. “A lot of bad things happened in Texas,” Nelson disclosed. “[And] there wasn’t anywhere to go when I came back [to Ojai],” she said.

Nelson has a bright personality and a positive outlook. I met her in a small room in Kent Hall (a building on the City Hall campus), which has been transformed into the camp’s “coffee room” — it also has a microwave and a small refrigerator. It’s a common gathering place for City Hall campers.18

“I’m very thankful to be here,” Nelson told me, sitting in the coffee room with her cane in hand and dog at her side, “there’s a lot of sweethearts here.” Prior to living at City Hall, Nelson camped at Lake Casitas. She initially was afraid to come to City Hall, she said, but was pleasantly surprised with the community she found. “The old ladies are cool. The younger ones just can’t get enough of partying,” she said. “It’s not too bad except when it rains a lot.” Nelson, who slept on the floor of her tent at Lake Casitas, has a twin bed in her tent at City Hall — a donation from a community member. “I slept better than I literally had in months,” Nelson said of her first night in bed, a bright smile on her face. “I love Ojai. Everyone helps so much.” Nelson’s daughter, who works locally, visits her often.

SOLUTIONS: WILDERNESS TENTS AND A $12M HOUSING PROPOSAL

“This by far is the most we’ve ever seen the City of Ojai involved [on homelessness], I think a lot of it is that it’s literally in their backyard,” said Jayn Walter, co-Executive Director of the HELP of Ojai.

Indeed. The City Council unanimously identified homelessness — specifically, the camp adjacent to City Council Chambers — as a top priority in August 2023. A month later, the Council ok’d expenditures of up to $200,000 to “manage” the encampment.

Raine was hired using that budget. The city also used the fund for temporary bathrooms and hand washing stations to serve the campers. Meanwhile, a concerned group of residents known as the Ojai Homeless Taskforce actively engaged with city staff — including former Interim City Manager Mark Scott, even after he left town — and experts from the HELP of Ojai and Ventura County Continuum of Care to identify solutions. The solution they found is one of Newsom’s key initiatives: the $750 million Encampment Resolution Funding (ERF) program.

The program’s goal, according to the Governor’s office, is “to move unhoused Californians from encampments into housing.” Critically, ERF dollars may only be used to fund “proposals… with clear pathways to permanent housing or [that] place people directly into permanent housing.”19 Are you sensing a challenge here?

Thousand Oaks and Oxnard each won ERF funding in 2023, $5.8 million and $4 million, respectively. Both cities are using the funds to move homeless folks out of encampments and into temporary shelters. Wait — that doesn’t sound like permanent housing, right? According to Jennifer Harkey, the Program Director for the Ventura County Continuum of Care,20 Thousand Oaks and Oxnard were able to win ERF funding for temporary housing because both cities have separate “motel conversion projects” in the works. In other words, both cities can demonstrate a clear path to permanent housing.

The matter of the camp came before the Council once again on December 12th — it was the same night they approved 50 units of affordable housing21 on Bryant Circle. It was also the night of a controversial vote to close the city’s pickleball courts. In between those two headline actions, the Council authorized city staff to work with the Taskforce (and Harkey) to prepare an ERF grant application for submission by January 31st (the funding cycle deadline). The Council also agreed to phase one of a strategy to relocate the camp and transition campers out of the dirt and into heavy-duty “wilderness tents” on city parking lots.

“That was probably the easiest thing we’ve ever done,” Mayor Betsy Stix said with a smile after the Council voted unanimously to approve the tents’ locations and the staff work on the ERF grant application. “I just want to compliment us, we’re on a housing roll tonight!” Councilwoman Rachel Lang added. They quickly moved on to the pickleball matter.

By the time the full ERF grant application made its way to the City Council for approval on Tuesday January 23rd, City Hall neighbors had caught wind of the December 12th vote. They were displeased for a few reasons, one being that they hadn’t been notified of the soon-to-be constructed tents, or the ERF application.

The full picture of the city’s plan to relocate the camp emerged that evening. The ERF grant application, written by Harkey, envisions a two-phased plan: phase one, as discussed, moves campers to heavy-duty wilderness tents located in city parking lots. Lockers will also be provided for the campers’ personal belongings. “These tents likely are something that will be in place and last anywhere from 18 months up to two years,” Alameda acknowledged.

Phase two of the project — if the grant application is approved — would involve an outfit called Dignity Moves, a non-profit organization that recently completed a 34-unit transitional22 housing project in downtown Santa Barbara. Ironically, the project’s next-door neighbor is a Morgan Stanley wealth advisor.23

Each of the tiny (64 square foot) single occupancy housing units has “windows, a bed, a chair, a desk, heating, air conditioning, and a door that locks.” According to the Santa Barbara Independent, the project has the look of “a groundbreaking new tiny home village.” (I’m hesitant to call these units “tiny homes,” because they don’t have a bathroom or a kitchen.)

Anyways — using ERF funding, the City of Ojai proposes to work with Dignity Moves to construct a “permanent supportive housing project” similar to 1016 Santa Barbara Street. The big difference between the two projects being the term “permanent.” Ojai’s proposal envisions 18 160-square foot single occupancy units, each with a sleeping space and a small living space. Alameda emphasized that even though the ERF application lists Kent Hall — both the parking lot and adjoining building — as the project site, it merely served as a “costing model,” and the development could be sited elsewhere.24

Amy Mendoza, a retired OUSD teacher who lives on South Signal Street, registered her opposition to the housing concept, which — as written — would be sited around the corner from her house. Mendoza told the City Council that she and her neighbors no longer feel safe in their neighborhood, due to the population of the camp:

“There have been two incidents on my street where an unhoused person has walked into my neighbors’ homes when they were present. This person currently is living in the encampment behind City Hall. They demanded to use my neighbor’s shower in one instance and do their laundry in the other.” Mendoza continued, “I have a neighbor who put up a fence to keep people from continuously trespassing in their yard. Two times I have arrived home to find a person in my backyard. The first time, it was a person who currently lives in the encampment, he was looking in my windows. When I got out of my car, he began incoherently yelling at me.”

“Our neighborhood has changed,” said S. Ventura St. resident Dave Chapman. “It never felt unsafe here until sometime last year. Noise now exists all hours of the day and night: shouting obscenities, screaming, fighting. I have called the Sheriff a number of times, but realizing that their hands are tied, have stopped doing that.”

“Another one of my big concerns is fire,” added S. Blanche St. neighbor David Patrick, “We have already seen a tree fire on a vacant lot near the encampment caused by individuals from the homeless encampment cooking.”25

The neighbors weren’t uniformly opposed to the use of Kent Hall as the ERF project site, however. Michelle LeClerc wrote in an email to the City Council, “I live nearby on Ventura Street. As a neighborhood resident, I support the encampment. Welcome to the neighborhood!”

After hearing from a host of City Hall neighbors, the Council voted 3-2 to submit the grant application the following week. Readers may wonder how the vote broke down…

Councilwomen Suza Francina, Rachel Lang and Leslie Rule each voted to move forward, arguing that submitting an ERF application wouldn’t bind the city to anything. “I just don’t see the downside,” Rule said. Lang noted that the grant funding could alleviate some of the neighbor's concerns — by providing resources for 24/7 security in the area. The application also includes costs for “health care and behavioral health services through the County of Ventura.” I should note, too, that as of the 23rd, the application budget wasn’t complete.

Still, Alameda and Harkey each advised the Council to vote to in favor of submitting the application, as ERF funding could be significantly depleted by the next application window — it’s a popular program with scores of applicants. However, Mayor Stix and newly-named Mayor Pro Tempore Andrew Whitman26 voted against applying for the funding at this time. They argued that there were too many open questions about the potential development’s location and cost — as well as too little communication with the neighbors. “We’ve had a gap of leadership on this issue since [former City Manager] James [Vega] left,” Whitman said, later referring to Scott as “the guy who walked out on us.”27

Harkey later confirmed that Ojai’s ERF grant application was submitted to the state at the end of January, with a complete budget. $12.6 million over two years.28 For context, Ojai’s 23-24 adopted budget is $14.9 million. Harkey said that she will meet with the City of Ojai in February to “consider alternate locations for the housing development.” ERF funding will be awarded by March 31st.

Regardless of the application’s success, phase one of the city’s plan to relocate the campers is ongoing. Saturday, January 27th was construction day for eight of the heavy-duty wilderness tents and storage lockers. According to Raine, approximately 75 community members showed up to help.

Seven of the tents — all of which will house elderly and disabled residents of the camp — were constructed in the Kent Hall parking lot. The final tent was pitched on a deck overlooking the City Hall campus — Raine received permission to house Nelson there due to her mobility issues. Her new tent is directly adjacent to the coffee room. “It is really exciting because everybody will congregate there and I love that,” Nelson said. I caught up with her after her first night in her new shelter, which she showed to me proudly. “I’m going to make it nice because it feels nice,” she said, grinning.

CONCLUSIONS

Nelson’s story is heartening, in a way. But I can’t end on that note. (Sorry).

Because I keep thinking back to two stories I reported on as an Ojai Valley News reporter. In 2016, it was an article about a man named Douglas Peckenpaugh. The next year, it was Thomas Taggart. Both men were found deceased near makeshift campsites in the City of Ojai. Their bodies were severely decomposed.

Peckenpaugh was a well-known member of the local unhoused community. As Ally Mills of the Ojai Valley Family Shelter told me after his remains were identified, “It's been something people have been thinking about. If it's not Dougie, who is it? Who else have we not seen for a while?”

That’s one thing to remember as the Supreme Court prepares to debate this community’s rights: homelessness is deadly.

If you enjoy these reports, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or making a donation. The most helpful thing you can do is very simple: share this work.

VCSO created its “Sheriff Homeless Liaison Unit” in 2021. It includes officers from around the county who have additional training in mental health and public services.

HELP of Ojai is local nonprofit dedicated to “fulfill[ing] the basic unmet needs of vulnerable Ojai residents.” They’re a critical service provider to the local homeless community.

A word on language: some argue that the term “homeless” has derogatory connotations and can be dehumanizing — particularly when it’s applied to an individual. However, the term is also widely used amongst people experiencing homelessness, and in government. I will use the term in this story, in addition to “unhoused” and “unsheltered.”

Conversely, sheltered homelessness “refers to people who are staying in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or safe havens.”

The unincorporated area consists of a broad swath of land that includes portions of the Ojai Valley, the Lockwood Valley, and multiple beach communities along the 101 Freeway.

To be clear, the city’s official count is 30. Raine acknowledged that the population ebbs and flows.

An ordinance is a local law.

The Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution reads, “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”

That is: Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon and Washington.

See what they did there? In short, the city tried to get around the Martin decision by not overtly banning sleeping in public, but disallowing the use of sleeping “paraphernalia” in public. Seems pretty cruel to me.

It’s worth noting that Newsom pledged to make homelessness his top priority… back when he was elected Mayor of San Francisco in 2003. This issue has colored his entire political career.

There’s a clear political divide at play: the two appeals court judges who upheld Martin v. Boise were appointed by President Bill Clinton. The one Trump appointee on the three-member panel dissented. The U.S. Supreme Court has a conservative majority. (Duh.)

I will note that the digital version of Ojai’s municipal code appears to be out of date — the “Right to Bodily Liberty for Elephants” ordinance, approved in 2023, is nowhere to be found.

The weapon was a motorcycle helmet.

I acknowledge that we have no working definition of “local.”

I also want to acknowledge that mine is not a representative sample size.

Due to her lack of income, she could no longer afford a storage space.

Setting up the coffee room was one of Raine’s first projects when he was hired to manage the camp. “Call it my ‘ice breaker’ with the campers,” he said. “When I started, I knew I was being eyed with suspicion by the campers who didn’t know me. I needed to gain their trust first. The coffee room is the hub of the camp. It’s where many come to first thing in the morning.”

This focus on “permanent housing” is part of a now-widely adopted philosophy known as “housing first.” This approach “prioritizes providing permanent housing to people experiencing homelessness, thus ending their homelessness and serving as a platform from which they can pursue personal goals and improve their quality of life. This approach is guided by the belief that people need basic necessities like food and a place to live before attending to anything less critical, such as getting a job, budgeting properly, or attending to substance use issues.”

Their mission is to end homelessness in Ventura County.

Wait, why can’t this be permanent housing for long-time Ojai unhoused folks? Because — basically — this project is relying on a different type of grant funding, Harkey said.

The bureaucratic term here is “interim supportive housing.” It effectively means “temporary.” Ojai’s ERF grant application calls for “permanent supportive housing,” sited on various City Hall parking lots.

One thing that is underlying this entire story: massive income inequality.

The state would have to sign off on the new location, however.

I can’t confirm these details, but I can confirm that the Ventura County Fire Department (VCFD) has responded to multiple illegal campfires in the camp.

This was it’s own little drama. Francina wanted to continue in the role and argued the Rule and Whitman would each be seen as “controversial.” Her motion to appoint Lang to the role died without a second. Francina and Whitman each voted for themselves, but Whitman had Lang on his side.

Newly hired Ojai City Manager Ben Harvey’s first day on the job was Jan. 29th. He was preceded in the job by Interim Manager Carl Alameda, who took over after Interim Manager Mark Scott resigned in November. Scott got the job after former City Manager James Vega hit the road for Port Hueneme in July 2023. Yes, Ojai has had four managers in the space of one year.

That number includes: “the modular housing development, interim sheltering costs, supportive services, security, maintenance, utilities, and grants administration (limited to 5% of non-development),” according to Harkey.

Appreciate your reporting.