Greetings Readers! I happen to be writing you on the 37th anniversary of my birth.1 So if you’re looking for a reason to become a subscriber or donate to support this work, this may be it!

Is This the End of Ojai Citrus?

Since January, I’ve interviewed about 30 farmers, farm workers, farm educators, ag regulators, scientists, and more. Selections from some of these interviews are on display at the Ojai Valley Museum, as part of an exhibit that asks: Does agriculture have a future in the Ojai Valley? The exhibit — which will be up until August 4th — also features photos by Peter Adams, which he graciously allowed me to use here.

… So? Does agriculture have a future in Ojai?

Here’s what I know for sure: the future will not look like the present (this is often the case). In the words of B.D. Dautch, owner of Cuyama Road’s Earthtrine Farm2, “Well, it's not going to get any better. And it can only get worse.”

I heard a lot of (fairly depressing) statements along these lines from the elders of Ojai’s farming community — particularly those who grow citrus. Here’s Emily Ayala, a fifth-generation farmer at Friend’s Ranches: “Unless there are some big changes, I really just see agriculture disappearing.”

Before we get into the why of these statements, let’s orient ourselves to the past. Here’s a short history of agriculture in the modern Ojai Valley, from Tony Thacher, Ayala’s father (and the grandson of Sherman Day Thacher). Thacher, now 84, has farmed in Ojai for the past half century. His wife (Ayala’s mother) is Anne Friend — the Friends began growing citrus in Ojai in the late 1800s. I had the opportunity to sit with Tony and Emily during a rainy day in January.

“Go way back [to] when [Americans] first moved to Ojai,” Thacher said over the noise of the rain. “Almost everybody in the United States was a farmer. They come out here, they buy a plow and a horse and they buy a sack of barley seed and they plow, ‘And my god, these rocks, [They think], ‘I guess we'll build walls out of 'em… Put 'em in a wall and we'll grow some barley.3’”

Thacher continued, “They quickly learned that it never rained in the summer, couldn't even predict it would rain in March. So they started going to tree crops. They grew apricots and walnuts and some of these things, widely spaced. And they knew how to dry apricots and they knew how to shell walnuts. And then that took too much money and they had to compete with people in Bakersfield area who could grow those things cheaper… And so then we ended up with citrus. And we grow really good citrus here and we're good at it. And the climate is perfect for it.”

However, citrus — which has become a symbol of the valley’s rural character, is increasingly difficult to grow in Ojai.

ECONOMIC STRESSORS

Let’s begin with the economic factors. As you may have noticed, real estate in the Ojai Valley is tremendously valuable. During our conversation, Ayala noted that an agricultural property on Ojai’s East End recently sold for $4 million. “That'll take 300 years of oranges just to pay the principal,” she observed. “Nobody that has bought land in the last 10 years is making money.”

That’s the thing: the folks with deep enough pockets to afford agricultural land in the Ojai Valley are probably not farming to make the bulk of their income — the math just doesn’t work. And that’s a different orientation than Ayala’s. “Some of the newer sort of farming people in Ojai, I view them as landscapers, not farmers,” Ayala said. Farming, in this model, is more of an aesthetic than a career.4

“Nobody who is doing citrus doesn’t have familial wealth,” added Jim Churchill, one of Ayala’s fellow Ojai Pixie farmers, “I include myself. We all started on second base.”

The cost of land is not the only economic factor at play here: profit margins for wholesale agricultural products haven’t kept up with rising costs, to put it mildly. According to Jim Finch, a third-generation Ojai citrus farmer, “Returns on lemons last year were the same as 1976, with our costs being 2023 costs, not 1976 [costs].” Finch also cites global competition as a challenge — that includes lemons from Argentina, avocados from Mexico, and oranges from Egypt. According to the USDA, Egypt is now the world’s number one orange exporter.5

Ojai’s agricultural products, too, make their way around the world. Ojai Pixie tangerines are a favorite in Japan. “The Japanese customers will specify Ojai when they're importing from Sunkist,6” Churchill said. Approximately two percent of Ojai’s 2024 pixie crop will make its way to Japan — it’s about the same amount of pixies sold in Westridge Midtown Market each year, Ayala said.

Another challenging trend mentioned by multiple farmers — citrus and otherwise — is the corporatization of agriculture. Jurgen Gramckow, who grows tangerines in historic Rancho Matilija explained:

“Agriculture is not a small-time family business anymore. You’ve got to be corporate, you got to be big. Most of these guys that are successful, they have production in Salinas, they have it in Santa Maria, they have it here in Oxnard, they have it in Mexico, they have it in Yuma. If they're selling romaine lettuce, they're selling it 12 months out of the year — it just comes from different places. You’ve got to be multi-location so that you can have continuous supply.7”

Ayala provided a similar perspective. Another important point about Ojai’s farms: they’re small.

“[Ojai's] big properties are 40 acres. You talk to growers in the Central Valley and they're farming a thousand acres,” She observed. “All of Ojai's farms are owned by families… unlike some other parts of California where big swaths of land are owned by insurance companies. There's some university pension funds that have bought land. A lot of it is speculation. They're not necessarily trying to make money on the farming aspect, they're just holding onto the land or the water rights because it's a valuable investment.”8 A recent USDA survey confirms that in California, the number of individual farms is falling. Each farm’s acreage, however, is on the rise.

So, while it makes increasingly less sense to grow wholesale agricultural products in Ojai (consider Finch’s lemon returns) — locally produced “boutique-style” products utilizing the Ojai brand continue to be successful.9 The Ojai Pixie is the foremost example. As the classic bumper sticker declares, they are indeed “sweet, petite, and great to eat.” Just as important is the name “Ojai.” It’s a brand.

The Ojai Valley is a brand across product categories. Clothing. Cookies. Furniture. All manner of things that have little or nothing to do with the valley. There’s an Instagram account devoted to this topic. Pepperidge Farm’s newly-released “Ojai” cookie provides insight into the value of the Ojai brand and the ease with which a company can slap a community’s name onto an unrelated product.

Pixies are far from the only example of an agricultural product leveraging the Ojai brand. Consider the Ojai Olive Oil Co. Owned and operated by Phil Asquith, the business began as a retirement hobby for his parents, Alice and Ron Asquith. During Phil’s childhood, the elder Asquiths grew citrus and avocados on Carne Road.

During a fateful walk around their East End neighborhood, Alice and Ron wandered up Ladera Road and discovered an abandoned olive grove. No one had cared for the property in years, and still, the trees were loaded with fruit, Phil said. So, “bit by bit they started taking out all the orange trees on that [Carne] property and replacing them with olives,” Phil recalled. “Growing oranges and selling them to Sunkist just wasn’t as romantic.”

Alice and Ron eventually purchased the Ladera property — it was originally planted by a Danish family in the late 1800s, Phil said — and the Asquiths began selling their olive oil at the Ojai (Certified) Farmer’s Market during the late nineties. “We would run out in June,” Phil remembered with a smile.

As Phil got older, he began a career not in farming, but in finance.

“Honestly, the only reason I did that finance work was just a means to an end. I just wanted to make enough money so that I could live peacefully on a farm,” he shared. “Every penny I'd made throughout my twenties and thirties ended up going into this. But now it works. Now the business is actually profitable.”

2023 was the Ojai Olive Oil Co.’s biggest year yet. “We just made a staggering amount of olive oil [last] year. 6,000 to 7,000 gallons of olive oil. We had to buy shipping containers just to store it.” And more olive trees are coming online every season. Phil and his father — before Ron passed away in 2013 — expanded olive production beyond Ojai. Today Ojai Olive Oil Co.’s olives come from Malibu to Santa Ynez, and farms in between.

Now, olives themselves are not terribly profitable. However, “if you can convert them into olive oil, then there's more money to be made,” Phil explained. “But of course, you need to have a business and a brand.” In this case, both are strong. The Ojai Olive Oil Co. business is buoyed by an experiential element: they regularly host visitors to their on-site tasting room, which also includes homemade balsamic vinegar and skin care products. In short, it’s an agricultural business with a tourist element. And business is booming.

CLIMATE STRESSORS

Here’s another thing you may have noticed about this little valley10: extreme weather events are increasing in frequency, just as climate scientists foretold. This is not a problem for Asquith’s olives, however — they can tolerate temperature shocks in either direction.

“Freezing is a non-issue,” he explained. “It could snow here and the trees would be perfectly fine. They can handle the full range of the swings. And we will get days here where it's 115 degrees and you can look at other plants and just watch them withering and the olives are perfectly fine.”

While Asquith’s olives don’t mind the heat, Roger Essick’s avocados suffer — he farms on a hillside above Asquith’s property — it’s part of the historic Ladera Ranch.

“When we have those prolonged times where sometimes we have like five, six days in a row that are over a hundred, avocados hate that.” Essick explained, “We're trying to grow avocados in a place they don't really like to grow. It's a struggle. And it was that way in the beginning. And I think it's even harder now.”

“The valley used to get a lot colder in the winter,” Essick, who also serves as the president of the Ojai Valley Land Conservancy, continued, “When I first started doing this in the seventies, we were probably doing frost protection 20 nights a year.”

He recently planted a new variety of avocado due to rising temperatures, it's known as the GEM. “We're trying that mainly because of the possibility that it'll handle the heat better,” he said.

Heat, however, is not Essick’s primary concern. That would be water. Remember: there are two primary sources of water in the Ojai Valley: Lake Casitas11 and the Ojai Basin. Some 150 wells draw water from the basin, many of which serve agricultural properties like Asquith’s. Others, like Essick, rely on Casitas water — and it can be costly. “Casitas rates have gone up tremendously,” he explained. “So we've already started taking citrus and avocado trees out.” Citrus and avocado trees, he said, require approximately the same amount of water.12

“I don't know if you've noticed in the East End, there's a lot of citrus coming out,” Essick added. “And a lot of that is water-related because those are people who don't have good wells. There's no way you can afford to grow oranges on Casitas water. It's just way too expensive.”

Thacher offered a similar observation, suggesting that if someone took aerial photos of the East End of the Ojai Valley — which has been dominated by orange and avocado orchards for the past century — you’d notice that with each passing year, the image shows fewer trees and more dirt.

And since we’re talking extreme weather, let’s consider the 2017 Thomas Fire, which formed a literal ring of flames around the valley and destroyed approximately 100 structures in the Upper Ojai Valley — in December. In Ayala’s view, irrigated orchards like Essick’s can (and did) stop the fire’s march to the valley floor.13 “My fear is when citrus is gone and the next fire comes in the next 15 or 20 years,” she said.

Still, Essick’s experience demonstrates the utter unpredictability of agriculture.

“No one really saw this coming in the fifties,” he said, gesturing to his hillside avocado farm. “When Casitas was formed14, they had to classify lands as whether they were ever going to be productive from an agricultural standpoint. And these [parcels] were not classified that way. There was no practical way [to farm here] until drip irrigation came along.”

“The future of agriculture in Ojai, who knows? Because this was all considered unplantable in the fifties,” Essick added.

PESTS, PESTICIDES, AND ANOTHER EXISTENTIAL THREAT TO CITRUS

Let’s move into a more controversial piece of this story, shall we? One of my primary observations over the course of this investigation is the clear split between conventional and organic farmers, and those who buy their products. Multiple organic farmers made clear that they consider synthetic pesticides tantamount to poison. “For food stuff, you just don't want to be using poisons,” observed Adam Tolmach, the farmer behind The Ojai Vineyard. A conventional farmer like Thacher, on the other hand, will retort, “If what we're using for pesticides is so bad, how come some of us farmers are so damn old?”

The pesticide15 conversation is particularly timely due to the existential threat of Huanglongbing (HLB), also known as the citrus greening disease. Let me run you through a little background here: HLB is a fatal citrus disease carried by a small, aphid-like insect known as the Asian Citrus Psyllid (ACP). The psyllid, which originates from southern Asia (as does citrus), feeds on the leaves and stems of citrus trees. That’s how infected psyllids spread HLB — which causes infected trees to, “bear small, asymmetrical fruits which are partially green, bitter, and unsalable.” Even worse, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA), “infected trees die within three to five years.”

HLB has already wreaked havoc in the United States: after the disease made its way to Florida twenty years ago, the state’s citrus production decreased by 75%. There’s no known cure.

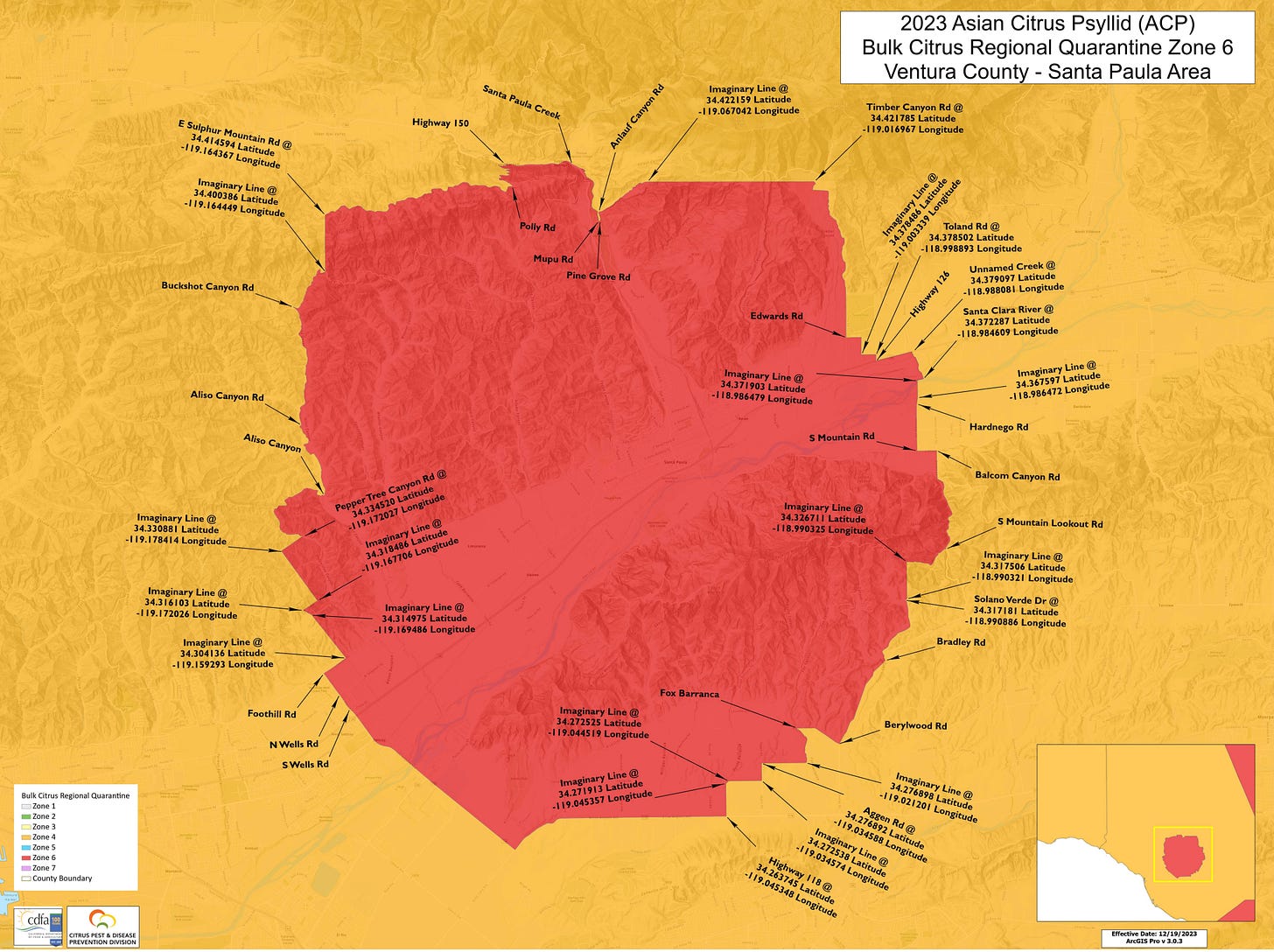

Psyllids are well-established in Ventura County, and unfortunately, HLB was detected in two Santa Paula citrus trees late last year — the first documented HLB infections in Ventura County.16 Since then, some 70 HLB-infected backyard citrus trees have been identified in the area. No HLB has been detected in any Ventura County commercial citrus orchards — yet.

Santa Paula is now under quarantine to prevent HLB-infected psyllids from moving to other areas of the county. The quarantine has no set end date, confirmed Victoria Hornbaker, the director of CDFA's Plant Health and Pest Prevention Services Division, because of the “long latency period for the infection to actually show up in the plants or in the trees.” The quarantine’s northwest boundary currently ends at Sulphur Mountain Road.

What does this mean for Ojai? Some local farmers, Ayala included, voluntarily participate in Ventura County’s ACP-HLB Task Force — the group’s stated mission is to delay the introduction and potential spread of HLB across the county while scientists work to find a cure. That means killing as many psyllids as possible via a coordinated pesticide program. These treatments occur three times annually, though organic growers are encouraged to treat their orchards more frequently.17

What kind of pesticides are we talking about? CDFA recommends growers use one in a University of California-approved list of options proven to eliminate (i.e. kill) psyllids. Maureen McGuire of the Ventura County Farm Bureau confirmed that the task force does not recommend a specific pesticide, but encourages growers to use what works best for their own needs — there are synthetic and organic options.

Some of the UC-recommended pesticide treatments are applied to the leaves of citrus trees, while others are applied to the soil below. Ayala informed me that growers in Ojai who choose to treat for ACP generally use the “foliar” option (the pesticide is sprayed directly onto the tree’s leaves). She confirmed that Friend’s Ranches are using Tempo SC Ultra treatments to keep psyllids at bay. According to the product label — which is approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)18 — Tempo SC Ultra is known to be extremely toxic to bees and aquatic life.

Churchill and Dauch, both organic farmers, choose to use the organic pesticide Entrust SC (another UC-approved option). “We do as little as we can and as much as we have to,” Churchill said, noting that he also uses horticultural oil to banish psyllids. A review of the EPA-approved Entrust SC label contains similar warnings to those on the Tempo label: the product is toxic to pollinators and aquatic life.

These pesticide treatments are all voluntary — for now. And according to McGuire, Ojai farmers are participating in the coordinated pesticide program at a much lower rate than other areas of Ventura County.

The case against pesticide use is laid out in a 2023 documentary film by local filmmakers Rebecca and Josh Tickell: Regenerate Ojai. The film, narrated by actress Laura Dern and produced in partnership with the Environmental Working Group, presents Ojai as an idyllic small town with a dirty secret: pesticides.

Dr. David White, program director of the local nonprofit Once Upon a Watershed was featured in the film. “A little of the spraying of the citrus that we’re concerned about now is to control the vector for [the citrus greening] disease, the Asian Citrus Psyllid,” he says.

I had the opportunity to talk to White further. “I question the emphasis on spraying,” he explained, “because the Asian Citrus Psyllid is here and we can't really get rid of it.” Instead, White supports “increasing biodiversity and supporting species that are going to be out-competing the psyllid.” The other piece of the solution, according to White, “is moving away from growing citrus.”

Farm educator Grace Malloy — the woman behind Meiners Oaks’ Poco Farm19, shared a similar perspective during a spring interview. “Eradicating a pest is not a thing. That's never something that has worked for humanity,” she asserted. Malloy’s 4-acre “learning farm” was previously an orange orchard — and she’s slowly removing the orange trees. For her student visitors, the remaining orange trees “bring up a lot of good learning opportunities to talk about how much water it takes to produce one orange.”

If HLB does make its way into the Ojai Valley, Malloy’s decided that all of Poco Farm’s remaining orange trees will come out. She wants to avoid pesticide treatments at all costs. “I cannot have kids around even the organic [pesticide]. I can't do it,” she said.

Regenerate Ojai also features farmworkers and local homeowners (including Dern’s mother, Diane Ladd) who say their health has been harmed due to pesticide exposure. Two women in the film also testified that their dogs died as a result of exposure to the chemical abamectin. Two pesticide treatments containing abamectin — Agri-Flex and Agri-Mek — are included in the UC-approved list of pesticides proven to eliminate psyllids.

Regenerate Ojai is not the sole driver of pesticide skepticism in the Ojai Valley: this is an ideological split that has hardened over time. The film is just one manifestation. Essick — who has navigated this conflict during the years he’s led the OVLC — likes to tell a story about applying a minor mineral solution to his fruit trees. He periodically hired a helicopter to drop zinc and manganese mixed with water over his orchard — the mixture essentially functions as a fertilizer, he said. “Every time we did it,” Essick explained, “the neighbors would bombard the ag commissioner’s office with calls and complaints.” He added, “The helicopter pilot, they won't even fly in Ojai anymore… you should hear the expletives.”

There’s another part of this story that could inflame tensions further: if (or seemingly, when) an HLB-infected tree is discovered in the Ojai Valley, pesticide treatments become mandatory for residents and commercial growers in the immediate area. Under a CDFA action plan, HLB-infected trees must receive mandatory pesticide treatments prior to being destroyed — that was the fate of the 70 backyard citrus trees in Santa Paula.

“If a [citrus] grove is located within 250 meters (820 feet) of an HLB-positive tree detection, the grower is required by law to treat the designated area with conventional insecticides to best manage the pest,” Hornbaker explained. In this scenario, organic growers could be required to use conventional pesticides.

I asked Churchill what he thinks about HLB’s proximity to the valley. “There are some things that I just close my eyes [to]… I wouldn't say I'm not overly worried. I'd say I keep my head in the sand a certain amount because I like to sleep.”

THE WORKERS

Enough about pests, let’s talk about people. Next, we’ll examine Ventura County farm labor through the experience of one family: the Magañas.

Juvenal Magaña Sr. came to the United States from Michoacán, Mexico in the late 60’s. He was barely a teenager. Magaña Sr’s son, Juvenal Magaña Jr. explained, “They brought him over because 13 years old was kind of working age. I don't think he even went to school when he came here. They [all] just went to work [in the fields] because it was easier for them to travel together.”

The Magaña clan eventually settled in Ventura County — for practical reasons. “Ventura County's weather allows for the harvest seasons to be longer,” Magaña Jr. said. After settling in Ventura, “they didn’t have to travel so much.”

After years of working in and around the Ojai Valley as a laborer, Magaña Sr. became the foreman of his labor crew, leading harvesting operations at properties like Essick’s. “We really liked [the Magañas],” Essick recalled. “They were working for another [labor] contractor and they wanted to go out on their own. And so we told 'em, ‘Hey, we'll give you all of our picking.’” The year was 1994. That was the beginning of Magaña Labor Services.

Magaña Jr. was a Santa Paula High School student at the time. “I had every weekend to work in the fields,” he remembered, “Every Saturday, Sunday, every summer vacation.” Today, Magaña Jr. is the vice president of Magaña Labor Services. His father is the president.

I cannot overstate the Magaña’s impact on the Ojai Valley. The vast majority of seasonal citrus harvesters in Ojai are affiliated with Magaña Labor Services, and the bulk of those workers were recruited from Mexico by the Magañas. But it wasn’t always this way.

“In the past, there was a lot more labor in the area. But the citrus harvesters in the area, they're getting old, and it seems like the newer generations are not really wanting to work farms,” Magaña Jr. explained. By 2017 — struggling to hire domestic farmworkers — the Magañas began utilizing the U.S. Department of Labor’s H-2A temporary visa program. The program allows U.S. employers to hire agricultural workers outside of the United States, provided that “there are not sufficient [domestic] workers who are able, willing, qualified, and available.”

During the first few years of recruiting agricultural workers from Mexico, the Magañas set up job fairs in Guadalajara — a central location west of Mexico City — to meet and interview prospective employees. Now, “at this point, we've met so many people that the spots are very limited and we really don't have to do that,” Magaña Jr. explained.

For the 2024 harvest season, the Magañas brought approximately 500 laborers into California on H-2A visas, all of whom will return home in the fall. These workers — primarily men — earn $19.75 an hour for their labor. I asked Magaña Jr. to describe what a day of harvesting work feels like.

“It's tough. It's heavy, but with the people around you, you have fun. There's music playing and people talking to each other. A lot of joking around and it makes your day go by faster. A lot of singing. It's hard work, but it's a rewarding type of work.”

Magaña Jr. and I also talked about pesticides and pesticide exposure.

“I mean, there's a lot of unknowns,” he said. “We don't know exactly what's going to happen 20 years from now some people or 10 years from now. All we can do is use the standard operating procedures for the safety of the workers. That's really all we can do is just abide by those.”

As far as he knows, he said, none of his family members have been directly impacted by pesticide use.

The state of California does document illnesses related to pesticide exposures, though the most recent data comes from 2019. According to a report from the California Department of Environmental Protection, 312 farm workers were injured by pesticide exposure in 2019.

Preparations for the 2024 harvest began in October of 2023. That’s when Magaña Jr. spoke to farmers like Ayala, Finch, Essick, and Churchill about their labor needs for the coming year. Once they have an understanding of — approximately — how much work is needed in coming season, the Magañas begin their recruitment cycle in Guanajuato. Citrus harvesting work generally begins in February. However, weather can get in the way.

The first two months of 2023 provide a good example. That’s when the Ojai Valley received more than its annual average rainfall over a period of eight weeks. Ayala — expecting to begin harvesting in early February — had signed a labor contract with the Magañas the previous year. The work was not what either party expected.

“These poor guys came up from Mexico last year,” she remembered, “There were 30 of them: two crews of 15. And we had them out here shoveling mud. That's not what they thought they were going to do in California.”

Her anecdote underscores the risk and uncertainty inherent in the field.

“What if there's a freeze?” She hypothesized, “We've already signed a contract that we will provide 30 hours of labor a week for two months, and we will pay that even if we have no crop.”

Now, not everyone working the 2024 citrus harvest is here on a temporary visa — it’s a far more diverse bunch than that.

Carlos Diaz is a 20-year employee of Dautch’s Earthtrine farms. A native of El Salvador, Diaz lives with his wife and two children on Dautch’s property. As we walked around Earthtrine’s rows of organic vegetables, culinary herbs, and fruit trees, I asked Diaz about the differences between farming in Ojai and El Salvador.

“In my country, we only have one season,” Diaz told me in Spanish. “It’s all corn or it’s all beans. There’s a lot of variety here.” He did farming work in El Salvador until he was ten years old, he explained. “Pero después de 10 años, yo paré ser eso. Y yo trabajaba en construcción.” Translation: “But after I was ten, I stopped doing that. And I worked in construction.”

One thing about agriculture generally: there’s a shocking diversity of experience on display.

Over at Churchill’s orchard, I met a collection of citrus packers — their job begins after the harvesters complete their work. El Camino High School Student Adi DeClerc — who’s 16 and delighted to earn an $18 hourly wage — described her job to me:

“We lay out the fruit, we look through it, we grade it based on rot, on greenness, on if it's fresh. It's like overall, ‘Is it good enough to sell? Will it last a couple of days of travel? We study the skins, we study the color. Whatever we don't sell usually goes to the farmer's market.”

DeClerc’s fellow citrus packers included Patricia Bautista, a 20-year Ojai resident who recently lost her restaurant job, and Colleen Tabrum, a retiree who has worked on and off with Churchill since the beginning. During a break, the three women — separated in age by at least 50 years — chatted using a mix of English and Spanish.

CONCLUSIONS

It seems clear (to me, at least) that postcard images of Ojai in the future will contain fewer orange blossoms. But what will take citrus’ place?

We know that the modern economy prizes land in Ojai, primarily because people want to put homes on top of it. Here’s another colorful observation from Thacher:

“We got this really valuable commodity under our feet that we farmers know how to do one thing with. And [real estate] developers know how to do another thing with it, and they're like the ducks at the county fair. They just come around and you got to shoot at 'em again. You're never going to lose somebody coming along and wanting to develop parts of Ojai. Never going to lose that pressure.”

That pressure is undeniable. However, Ventura County does have protections in place to preserve open space: it’s called SOAR. The SOAR ordinance (Save Open-space and Agricultural Resources) states that land zoned20 as "Agricultural," "Rural" or "Open Space" can only be repurposed (re-zoned) via a vote of the people, or a vote of the Ventura County Supervisors. That means a zoning change in the unincorporated Ojai Valley21 could theoretically occur with three supervisor votes in favor.22 This ordinance is far from bulletproof.

I had the opportunity to speak with California Assemblyman Steve Bennett on the topic, he’s a former Ventura County Supervisor and one of the architects of the SOAR ordinance. Charmingly, he once taught economics at Nordhoff High School. I asked him about potential loopholes in SOAR. He did not provide a specific answer.

“It is a unique valley and an extremely precious resource,” Bennett said, “And you can lose that unique semi-rural feel any place if you're not careful. But it's mostly about local leadership and local people rallying together to protect the valley.”

Another important consideration: the state of California is incentivizing building statewide in response to the housing crisis.

Bennett continued, “If you look at agriculture, not just in the valley, but the prediction of the demise of agriculture has been made many, many times in many situations. But the one thing about people in agriculture is that they're extremely resilient, extremely adaptive, and what didn't seem possible in one decade suddenly becomes possible in another decade.”

Bennett’s final sentence takes me back to Essick’s story about his once “unplantable” avocado orchard.

And folks, we’re going to end right there. As always, thank you for being here.

Special shout out to my mother, Michelle Thomas. Thanks for birthing me!

I asked about the origin of the farm’s name: “I'm a Virgo. My wife's a Capricorn. My oldest son is a Taurus,” Dauch explained. “We're the three earth signs. So we form a triune or a triangle.” Awesome.

The soil on the east end of the Ojai Valley is notoriously rocky, hence all the rock walls.

If you wish to become a modern-day Ojai citrus farmer, you must first star in a hit sitcom. (This is a joke, mostly)

Those Egyptian orange trees, by and large, are fed by the Nile River.

Approximately ⅓ of Ojai Pixies are picked by Sunkist, according to Ayala.

Another theme that comes up throughout this piece is how modern eating habits, in some ways, demand globalized agriculture. If we want to eat romaine lettuce 12 months out of the year, we’re going to — by necessity — support business operations that are large and multi-location. Or rely upon a greenhouse.

A great example of this is up and over Highway 33 to the Cuyama Valley, where an investment arm of Harvard University’s endowment fund purchased land, planted nearly 900 acres wine grapes, and drilled 16 new wells for irrigation. The area gets about 8 inches of rain annually — water is in short supply.

I call this trend the “boutique-ification” of Ojai agriculture.

I’m sorry, I can’t help it.

It’s a man made water reservoir that receives water from Coyote Creek and Santa Ana Creek.

For the record: both citrus and avocado trees are more water-intensive than olives.

I’ll also note that Asquith, and his neighbor Connor Jones of East End Eden played a role here, too. According to Asquith, fire crews utilized water from a retention pond he and Jones created in order to extinguish the flames.

1956

We’ll be talking about “insecticides” specifically in this section, but I’ll use the catch-all term “pesticide” for clarity.

HLB-infected trees have also been documented in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego counties.

The organic options aren’t as long lasting as the conventional varieties.

Fun fact: earlier in my career, I did communications work on at EPA as a member of the Obama Administration. My communications portfolio at included the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention (which has jurisdiction over pesticide issues). I learned a few things, including a) the Toxic Substances Control Act is riddled with loopholes and b) risk assessments regarding chemicals focus on “dosage.” The question is not if a substance is toxic, but how much a living thing can be exposed to over a lifetime without significant health impacts. Of course, this all presumes the chemical is applied according to the instructions on the EPA-approved label. As visitors to Ventura County parks have (devastatingly) observed, these instructions aren’t always followed.

Spanish for “small.”

A zoning map is basically a planning document that states where different types of land use is authorized, like housing, business, manufacturing, agriculture, etc. You can check out the county’s zoning map here.

Unincorporated, meaning outside of the City of Ojai. The City does not have its own SOAR ordinance.

Here’s language from the ordinance: “The Board of Supervisors, following at least one public hearing for presentations by an applicant and the public, and after compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act, may amend, without a vote of the people, the Rural, Agricultural, or Open Space land use designations to comply with state law regarding the provision of housing for all economic segments of the community.”